DACAmented

A Struggle for Belonging and Identity

v i s u a l i z i n g i m m i g r a n t P h o e n i x

Argenis Hurtado Moreno

March 2017

Sunlight pours down into Estefania’s olive skin as she stands in front of the camera in a dichotomy of awkwardness and poise. She laughs when I ask her to pose but nonetheless moves with ease into a state of stillness. Her deep velvet-red hair is bold and yet subtle, and is in a back-and-forth between straight and curled hairstyles throughout our photo shoot. Her clothing style ranges from grunge to bohemian. Perhaps these subtleties in change may seem inconsequential, but Estefania’s ease of fluidity is partly due to her necessity to be adaptive, something she had to master while growing up undocumented. I ask her to stand behind the gate of my house with her hands just barely peeking over. The moment is quick because the gate is scorching hot, but the meaning is timeless and accurately representative of Estefania’s life struggle; one foot in the door (or in this case, two hands), but not fully quite in. She is one of many DACAmented youths with temporary permissible status with no certainty to a pathway towards American citizenship (see "Becoming DACAmented" by Gonzales, Terriquez, & Ruszczyk. 2014).

Estefania and I attended Maryvale High School together but we had not shared much interaction aside from a brief moment during a football game when I was the school mascot and she wanted a picture with the Panther. We came in contact again in 2012 through mutual acquaintances. After bonding over our shared status as unauthorized, Mexican migrants we developed a well established friendship. She is partly responsible for why I became interested in the topic of the DACA experience.

My inspiration to conduct ethnographic interviews with DACA students stems from my interest in undocumented youth and sustainability. At first the idea of connecting these two concepts sounds incompatible, but sustainability and social sciences are interdisciplinary fields that profitably intersect with one another. My intent is to mimic the success of Rachel Carson’s, Silent Spring, and the manner in which she raised public health concern and gave environmentalists a platform to speak out against the use of pesticides on the American public. Contrary to Alfred Hitchcock’s classic Hollywood thriller, The Birds, Carson horrifies her audience with an opposite premise: the absence of birds.

There was a strange stillness. The birds, for example — where had they gone? Many people spoke of them, puzzled and disturbed. The feeding stations in the backyards were deserted. The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices. On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh. (Carson, p.2)

Carson’s story of horror puts us in an immediate environmental mindset; however, sustainability encompasses more than just ecological efforts. Sustainability draws from a trifecta of social, environmental, and economic fields. When we relate Carson’s missing birds to the voices of DACA recipients, we are gazing through the social sustainability scope. Before DACA, unauthorized youth struggled to attain social mobility. The removal of DACA would be a horror to the livelihoods of the 861,192 DACAmented youth, their families, and their place in society (see Migration Policy Institute, DACA Data Tools).

Currently the U.S. holds a population of 1,932,000 young adult migrants eligible for temporary legal status through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Arizona has 30,184 DACA recipients as of 2016 (MPI). With the Trump administration’s current political rhetoric surrounding Obama’s 2012 executive order, the future of DACA is uncertain (LA Times 2/16/17). DACA recipients share similar stories[1] of struggle and perseverance. Estefania’s is one such story. Just as we seek the sound of the wrens and canaries, we must seek to hear the stories of DACAmented youth.

Estefania: From what I was told by my parents, we came to the U.S. when I was 10 months old. That’s pretty much all I know, that and that we crossed the border in a vehicle.

I never actually felt different from anyone growing up. In high school, I was part of JROTC since the beginning of freshman year. My dream was to join the Army. I was very passionate about it. I think I found out I was undocumented my junior year when I was speaking to an Army recruiter. I told him I was interested and he told me I could not join. I didn’t quite really understand the reasoning for it. I knew I was from Mexico, but I did not know that my lack of legal residency would keep me from enlisting to serve the country.

Around the same month or so we had these college workshops to apply to colleges and fill out the financial aid forms. I wanted to attend Arizona State University but I knew my family could not afford to pay out-of-state tuition. I was one of two or three students that had to sit idly by and watch the rest of the class share this experience without me because attending my dream college was financially out of reach.

I felt at a loss and decided to speak with my guidance counselor. I told her about my plans to attend ASU, but she wasn’t very helpful. She basically just told me NO. She very condescendingly said I should aim lower, go to a community college. I was so angry! How dare she tell me that? I was in honors and AP classes. I was ranked highly in my school’s JROTC program. I thought I had done everything right, everything I was supposed to. It didn’t make sense. My options were limited, as if who I was and what I had accomplished didn’t matter because I was born on the wrong side of the border.

The conversation with Estefania began to intensify, and she began to get a little agitated as she recalled the interaction with her high school counselor. She continued to say:

Estefania: I had felt so out of place struggling to find out who I was, you know, like I’m sure every teenager goes through that. But what was different between my friends and I was that I was told I couldn’t do what I wanted. It felt like everything was being taken from me. I felt American, but that didn’t matter.

Estefania’s grappling with belonging and the challenges regarding her identity are clearly marked by how she defined herself versus the legality of how American policy defined her. Many unauthorized migrants in the U.S. arrive at an early age. To meet DACA eligibility, applicants must have arrived before the age of sixteen. As much as young people born in the U.S., Estefania is product of American culture. She has lived in Phoenix for over 24 years, nearly her entire life, and has participated in the American culture just as much as any other person born on American soil. Yet, the lack of a nine-digit number matters more than the human experience.

The concept of identity is difficult to fully grasp, but moreso for those who feel they are ni de aquí, ni de allá, neither from here nor there. Similar youth to Estefania have been molded by American culture at an early age. The moment Estefania found out about her status is a moment not too different for many unauthorized youth. Estefania went through the public-school system and excelled academically. She was so embedded into the American culture that she was willing to serve in the U.S. Army. She was one of many told they do not belong. They become delegitimized by the very system that enculturated them throughout their youth.

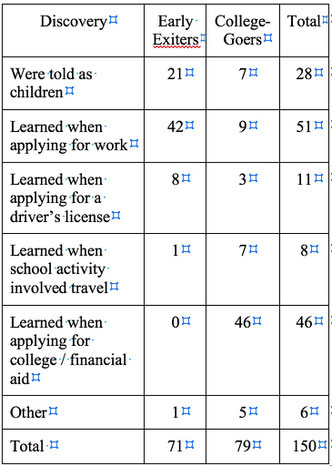

Sociologist Roberto G. Gonzalez, author of Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America (2015), discovers that for undocumented youth the moment of realization that they are not U.S. citizens occurs when they look to gain social mobility. This moment dictates new limits on the opportunities afforded to them. The following table is from Gonzalez’s book which displays when his interviewees (youth that exited the school system and those that continued) discovered their legal standing.

In his research, Gonzalez notes that for some undocumented youth the lack of social capital in the form of proper documentation poses a great barrier for them to continue on an academic pathway. Estefania was susceptible to not continuing her education beyond high school, but her resilience did not allow her to stop. She explains:

Estefania: A private university offered me almost a full scholarship. I think I only paid around $2,500 per semester. I graduated with a BS in Health Care Administration. And really it was the scholarship offer that led me to go into that field because that’s not really what I wanted to study. But it was a four-year degree, and it was going to allow me to move forward.

I didn’t really have a typical college experience because I didn’t feel I belonged and I had part time job that I worked under the table to pay for school. I was not eligible for a driver’s license and I didn’t have a car, so I had to take the bus and rely on rides to get to work and school on time. I had to manage my time wisely often at my social life’s expense. The time I could have spent participating in school activities like joining clubs or going to the games, was spent riding the bus, or working extra shifts.

I did everything by myself and it was tiring. My immediate family couldn’t really relate or understand because I’m the oldest and first to go to college. My cousins are all citizens so our college experiences were pretty different too. I didn’t have many friends there except for one.

But all that changed when I met someone in the same situation I was in. He was also undocumented. And he really was my emotional support to help me get through a lot of stressful situations. He would drive me to school and work and back. He was putting his own security at risk because he didn’t have a license either. But that was the person I depended on a lot. We got through things together. He was the only one that truly understood what undocumented life is like. He would even take me to the doctor when I was too stubborn to go because of how expensive it would be. Unlike my other friends, he was someone who I could talk to and I knew that he would understand my situation, wholeheartedly.

When DACA came around I was having difficulty accepting that I had to apply for this thing. It made it kind of official that I was different. I was basically born here, well at least I felt as if I was. So it took me a while to come around and actually apply for it. My new friend was influential in me applying because he had applied too, and he wanted me to have the same opportunities.

Estefania’s uneasiness at school stems from a lack of a supportive network. While surely Estefania was not the only DACA student at her university, many DACA students are not willing to disclose such information so in turn the opportunity for a DACA-supportive network decreases. However, for Estefania, she was able to create a bond with someone that motivated her. These types of networks enable DACA students to move forward, but are limited in many ways because they are codependent with one another as they tackle similar glass ceilings.

Estefania’s struggle to accept an identity she does not fully embrace or comprehend is not uncommon or surprising, because policies such as DACA do not provide a pathway to citizenship. Applying for DACA requires an investment of money and time. The process is draining and exasperating because applicants are required to submit various paperwork and documentation that proves continuous living in the U.S. Such a strenuous task is avoided by DACA-eligible youth because the costly process raises feelings of injustice. For Estefania, the fact that she has been in the U.S. since she was 10 months old created a sense of frustration and demoralization. She describes her experience as troublesome but rewarding:

Estefania: Going through the process of getting my DACA application filled out was difficult and then when I finally was approved I didn’t feel much different. I graduated college but still I worked at a dead-end job. I felt comfortable there, and I guess I was scared to move forward. But then the same friend began to push me to look for a different job. He would challenge me to apply to three jobs a day. I had put it off for a while. Then finally I listened to him. I applied to a position in social work and got it.

I really liked that job because I was working with first-time mothers and their babies from birth to five years of age. I felt fulfillment. But that was very short lived. I learned that while social work made me feel I was doing something helpful, it did not provide me with the economic opportunities I needed. I knew where I came from, and I didn’t want to stay in the same social class as my unauthorized immigrant parents. It sounds bad but it’s the truth. I know how hard they work but their income doesn’t reflect that. I also wanted to pave the way for my younger siblings. I had a lot of self-pressure to advance.

Currently I work at an insurance company. This job allowed me to move to a nice apartment in downtown Phoenix. I’m gaining my independence. My goal was to move out from my parents’ house before 25 and I was able to do that with one year to spare. I have my own car. So I’m not limited as much anymore, but that could all change too. So it’s hard to be too comfortable and confident.

When I wanted to move out from my parents’ house, the presidential election was happening. And I was really fearful of getting my DACA revoked. My friend was very supportive in enabling me to meet my goals. But at the same time, it didn’t remove the fear. Now that Trump has won the election I can no longer watch the news. It makes me sad because the news is really overwhelming and negative. DACA allows me to sustain myself for the time being, but that could be taken away at any moment.

Roberto G. Gonzalez perfectly encapsulates the fear Estefania described. In his book he notes, “Many indeed ‘grew up American.’ However, their everyday adult lives remind us that . . . they too are stigmatized, excluded, and offered only partial access to the American dream.” (p. 175)

DACA is an executive order established by former President Obama. To reduce the uneasiness DACA recipients like Estefania feel over the uncertainty of their status, a protection order should be established that prohibits the disclosure of DACA recipients’ information if the program were to end. Or better yet, since DACA recipients have thoroughly passed a background and fingerprint clearance they should be granted a pathway to citizenship. Such a policy would remarkably decrease the levels of insecurity and rejection felt by DACA recipients. Allowing them a pathway to citizenship will also provide a concrete sense of belonging and an established identity.

Before our interview is over Estefania adds:

Estefania: As cheesy as it sounds, I would like to encourage anyone in a similar situation to chase their dreams. If I had listened to my cranky, unhelpful, high school counselor I would not be where I am today.

Summer of 2017 will be five years since the introduction of DACA. To keep DACA going or to enhance its benefits, policies must change. DACA is a momentary answer to a bigger social problem. DACA is not fully sustainable because it requires applicants to renew their status every two years, does not qualify them for federal aid (healthcare, financial aid, etc.), and limits them to stay in the country (must apply for advanced parole, $575). DACA will not solve the complications of belonging and identity unauthorized youth face in America. Until policymakers agree on the legality of DACA, recipients will continue to find themselves in grey abeyance with the possibility of being silenced once again. Their identities as Americans, as well as their livelihood are at stake. DACA, like the initial use of pesticides, appears to be a good solution at first; however one must seek the long-term effects. DACAmented youth help boost the economy, Philip E Wolgin shows in "The High Cost of Ending Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals" (2016), and they have been enculturated into his country, so why give them momentary relief in which the struggle of belonging and identity is still a constant battle? DACA as a pathway towards American citizenship would be a more sustainable answer for migrant youth.